History

185 Liberty Street, Newburgh, NY

Prepared by Steve Baltsas, 2022

Description

185 Liberty Street is a two-and-one-half story cross gabled brick residence sited on a partial declivity between two later structures. Its eastern elevation, set roughly 8’ from the bluestone sidewalk, is three bays, the rightmost being a dominant gabled projection fenestrated, or given windows, in four stages.1 Beginning at the right, a brownstone water table skirts the base of the projection’s first floor bay window and ends at a concrete staircase accessing the wooden porch and entry.

The hipped roof porch, three bays wide and one deep, occupies the remaining space enabled by the projection, ending inches from the facade’s limit at left. Its supports are five chamfered posts, capped by molding; semicircles rest above and join a higher beam chamfered at each opening, the meeting places marked with carved paterae. Lower on the posts are balustrades of turned spindles, their height indicated on their flanking posts by chamfers. Beneath the decking are basement window openings; one smaller and rectangular forms the projection bay window’s base.

Above the water table, a paneled base for the bay forms, five-sided with three major openings. Panels for the latter are inset twice, with vertical single insets for the remaining sides that function as a point of connection between the masonry and bay as an independent fixture. It is corbeled with a curved roof, touching the second story brownstone sill shared by two initially 4/4 openings divided by a wooden mullion. Aligned with this, a narrow window overlooks the porch roof from the projection’s south side.

In the projection’s third story gable wall, congruous with the second floor openings, are two round-top 4/4 windows on a brownstone sill separated by brick. Window symmetry is likewise found in the remaining body of the house: starting at left, the projection’s second floor mullion openings are installed again for the first and second floor, all with brownstone sills and lintels, while the third floor is a single rounded window within a gabled wall dormer.

Considering the house’s central bay, holding the entry, a single initially 6/6 (now 1/1) window finds placement just above at the second floor, and higher, a small gabled dormer with a circular window. This originally 6/6 window is essentially stamped across the southern elevation three times on the first and second floor, twice on the basement level, and once in the third story gable wall. Being a variation of a jerkinhead roof, minus the truncated end, this gable slopes to create a flat peak and surface until the roof ridge’s intersection with the projecting gable.

All of the primary facade’s gables, excluding the central bay’s dormer, are mirrored on the rear elevation. Bargeboards are however limited to gables facing Liberty Street at the southern and eastern elevations. The bargeboard pattern is a raised zigzag: trefoils line the base, three-pronged Gothic piercings join at the fascia. An internal chimney is placed at the intersection of the projection and main house, as in contemporary Gothic Revival domestic works, but in the lingering Federal style, two external chimneys line the southern elevation. The roof is slated in alternating arrangements of polygonal and rectangular shapes.

Case for Attribution

Newburgh Architecture and Planning Before 1861

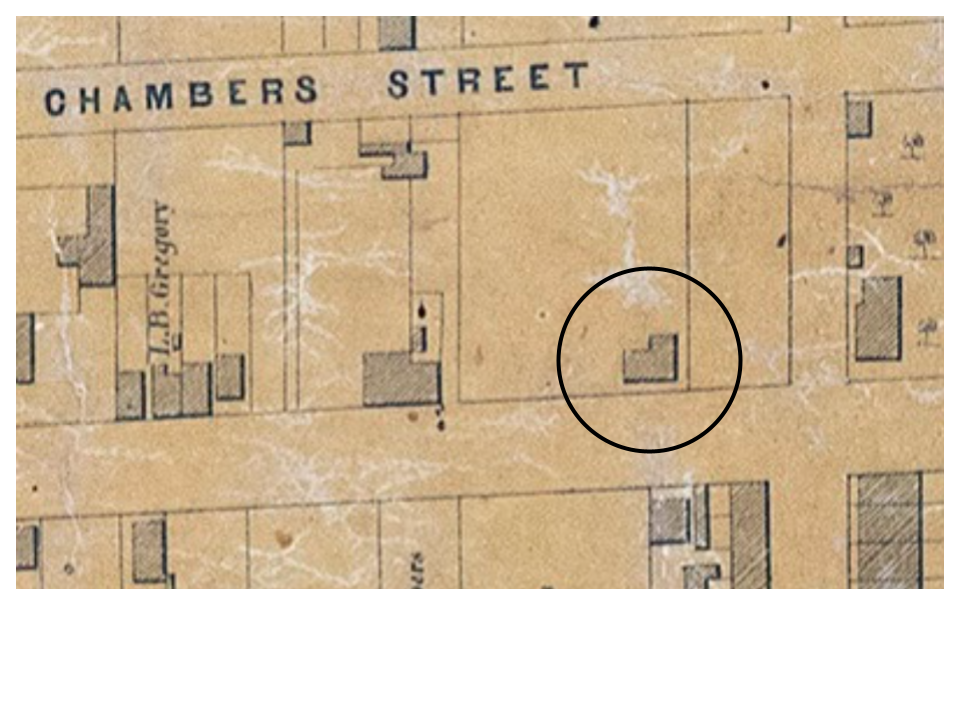

The house which is today addressed 185 Liberty Street appeared first on an 1854 map of Newburgh (Fig. 2), and soon after in the village directory as “149 Liberty Street.” New York civil engineer and surveyor William Perris, when visiting the Village of Newburgh to prepare this map, passed construction of the house and decided to include it. Perris records the house as forming the northeast corner of lands most recently in possession of the Gorham and Young families. Though not illustrated with the cross gable projection complete, the structure is deliberately set back from the streetline, a practice inevident on older streets nearer to the river, such as Smith or Water.

Figure 2 185 Liberty Street (circled) appears in William Perris’s 1854 Map of Newburgh.

Land west of Liberty Street at this moment came under serious consideration for residential development. Areas once considered rural, where wealthier families had parcels, were being sold off and divided. To the north, Grand and Montgomery Street became desirable for upper middle class residences. This latter street was, in the 1830s, branded “Highland Terrace” by the merchants who built their mansions there and effectively gentrified this ridge above the village. Moving into the 1850s, architectural patronage gained a seriousness with the incorporation of Downing & Vaux, the village’s first professional architectural firm. Whereas in previous decades carpenters and builders took commissions for many variants of architecture (houses, churches, stores) Downing & Vaux established their focus in domestic architecture—house and estate design.

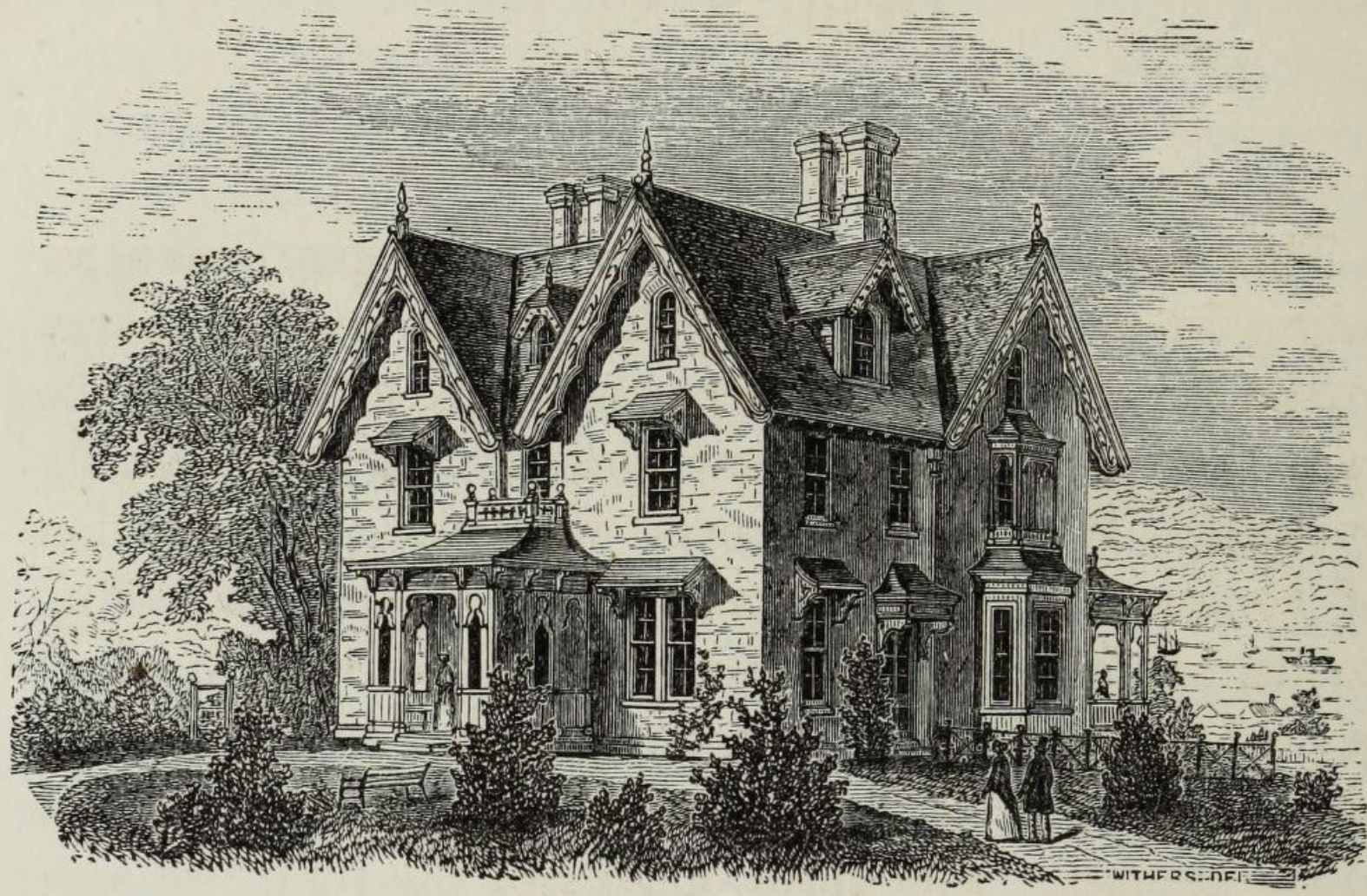

Figure 3 John Little, Nathan Reeve House (1849), 235 Montgomery Street, Newburgh, NY. (Tom Daley, Historical Society of Newburgh Bay and the Highlands)

Downing & Vaux was conceived by Newburgh native Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852) in 1850, who endeavored to create a “Bureau of Architecture” at his villa. In the summer of 1850, Downing toured England extensively, partly with the purpose of locating a suitable architect eager to help materialize his own theories and design ideas. He met Calvert Vaux (1824–1895) in London, then in his mid twenties. Capable as a designer and engineer, Vaux adapted his skillset to the Hudson Valley’s aesthetic. He and Downing shared architectural knowledge between themselves to control the firm’s output.

As early as 1838, Downing had provided architectural theory and advice to his friends informally. Though his first books, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841) and Cottage Residences (1842) catapulted the younger nurseryman and writer to national acclaim, his neighbors were not much moved to instate his preferred Gothic designs in the village.

Owing to the tumultuousness and economic depression of the 1840s, no major building boom erupted until the next decade. The few buildings completed in Newburgh in the 1840s—likely less than a dozen—had no true style. They were rectangular brick or frame boxes, tethered to earlier Georgian and Federal style building trends of the late 18th and early 19th century.

One exception especially relevant to the design of 185 Liberty Street is the house at 235 Montgomery Street, claimed by mason John Little to be his work in 1849 (Fig. 3).2 The client as Little recalled was Nathan Reeve, a lawyer from a resolute Newburgh family with means to build tastefully. 3 Little’s house for Reeve brought picturesque asymmetricality to Newburgh architecture through its cross gable form, right projection, and pierced bargeboard. Though the exterior is Gothic-leaning, the interior according to 20th century photographs had a Greek Revival finish.

With Downing & Vaux’s immediate prestige as house architects in 1850, carpenters and masons took notice of their models. Prosperity, especially encouraged by the opening of an Erie Railroad branch in Newburgh in January 1850, escalated the village’s finances, allowing for more building projects. Downing & Vaux saw five of their designs built locally:

- “Cedar Lawn,” the Joel Tyler Headley House (1850–51), New Windsor

- “Algonac,” the Warren Delano House (1850–51), Balmville

- William L. Findlay House (1851), Powell Avenue

- Dr. William A. M. Culbert House (1852), Grand and 2nd Street

- David Moore House (1852), Grand and Broad Street

The final house was influential on Newburgh builders for reasons discussed further. Downing’s death in late July 1852 set Vaux on his own for roughly a year and a half, when he at last accepted Frederick C. Withers (1828–1901) as his business partner. Before the formation of Vaux & Withers in late 1853 or early 1854, Withers was Vaux’s assistant and draftsman, brought by Downing from England in 1852. In the shock of Downing’s demise, Vaux had kept Withers as an employee first for the firm, and then in his own private architectural practice. Vaux & Withers operated from 1854 to the spring of 1856, when Vaux left Newburgh for New York City with his family.

These six years, 1850–56, were a “golden age” for Gothic in Newburgh. The style was practiced as Downing authorized, and had not been fully touched by his later German, vernacular Swiss, and Elizabethan aesthetics, nor had the writings of John Ruskin, later influential to Withers. Vaux’s hints at Asian and French architecture were incomprehensible to most builders and not rapidly adopted. As a designer without his mentor, Vaux felt a pressure to create his own variations and articulations of Gothic, his own clarity and refinement, as fellow English immigrants Gervase Wheeler and Richard Upjohn were doing. Americans under Downing’s influence, such as Henry Austin of New Haven or Luther Briggs, Jr. of Massachusetts, were likewise finding their own touch past the tastemaker’s death.

These were not the concerns of the standard builder in Newburgh. He was a man trained in organizational principles wholly based in classicism. He had no sense of the asymmetrical exterior or imbalanced floor plan, but was instead concerned with space and affordability. Even in the David Moore House (1852), Downing & Vaux attended the project working with an existing mundane square foundation and lifted a picturesque massing from it, aided, in Vaux’s admission, by added details such as window hoods. 4

Figure 4 Calvert Vaux and Andrew Jackson Downing, David Moore House (1852), 55 Broad Street, Newburgh, NY. (Vaux, Villas and Cottages, 1857)

James McClung, Builder

A Newburgh builder who would have straddled Downingesque design and the curriculum of an early 19th century house architect in the northeastern United States is James McClung (1815?–1905). In 1854, McClung built the house at 185 Liberty Street for his family; the house is here attributed to him.

In the early 1850s, McClung and his brother Samuel worked as builders in the firm S. & J. McClung, with an office on Water Street at the foot of Washington. Their competitors as listed in the oldest extant Village of Newburgh Directory (1856–57), were: Gilbert J. Bailey, Baughan & Brown, Andrew Little, and Thomas Shaw & Sons. The builder at this time handled architectural design, masonwork, carpentry, and general contracting. The carpenter handled woodwork, carving, production of fixtures, and even furniture. Under carpenters, Andrew Little lists himself again, but the names James Hutchinson, William Hilton, and John W. Boyd also appear. In Hilton’s instance, masonwork on projects was at times completed by his brother, mason John Hilton, or a trusted associate, though by 1859 Hilton considered himself a builder. A builder could feasibly design a house and construct it completely by hand, though most had training in engineering and craftsmanship rather than architecture.

Window Design

The lack of architectural finesse in McClung versus Vaux is evident in a house attributable to him through his association with 185 Liberty Street. Built ca. 1860, this brick residence, which stood across from the Union Presbyterian Church (now Ebenezer Baptist Church), is 185 Liberty in reverse (Fig. 5).5 We observe two similar means of fenestration, both copied from Vaux. The first is the appearance of a tripartite, or three-part window, its mullions, or dividing bars, made of wood. Vaux encouraged the use of tripartite windows in Downing & Vaux’s design practice, as they proved to be more visually stimulating than (contd.)

Figure 5 Attributed to S. & J. McClung, views of demolished house at 73–81 First Street (ca. 1860), Newburgh, NY.

Figure 5 Attributed to S. & J. McClung, views of demolished house at 73–81 First Street (ca. 1860), Newburgh, NY.

(Tom Daley, Historical Society of Newburgh Bay and the Highlands)

Figure 6 Paired first floor window with wooden mullion, Moore house. (Library of Congress)

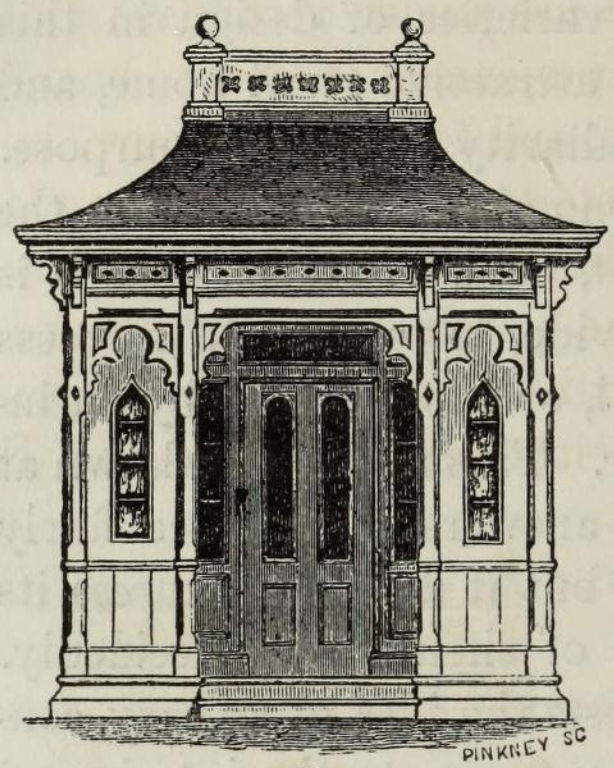

Figure 7 Vaux, Detail of porch, Moore house. (Villas and Cottages)

three windows placed beside each other without a direct relationship.6 The windows unified, serving as an organized rectangular mass, could be used as a base for windows or decorative elements above, such as in the bay window of this house’s projecting gable (Fig. 5). Window openings are able to breathe and decrease in multitude moving upwards; they are undulating, likewise from the gable peak downwards increasing with a pyramidal effect. The arrangement here is replicating one at the side of the David Moore House (Fig. 4), where windows increase as the eye moves down the facade.

McClung has a greater handling of this ca. 1860 than he does ca. 1854 with 185 Liberty Street, as the space between the third story paired rounded windows and second floor openings is one of disharmony, a misunderstanding of Vaux’s intention. By 1860, with greater training, we see he is able to duplicate and mix Vauxian elements, again primarily from the Moore house. The paired window with wooden mullion and window hood on brackets are present in both examples (Figs. 5 and 6). 7 Similarly, McClung considers the Moore house’s entry porch, with a curved, Asian-inspired roof, and adds it to the top of the rectangular bay. The top balustrade of his choosing functions as a tiny, purposeless balcony, a balconette, as it does on the Moore entry porch and side window arrangement. Though he retains the balustrade caps and side piers, the center panel he replaces with wood turned spindles from 185 Liberty in miniature. Above are paired round-top windows, like 185 Liberty, but shrunken to fit beneath the gable’s peak.

An uncomfortable discord exists in the McClung’s fenestration on the primary body of the First Street house, as a tripartite window is set above two spaced windows. Another sign of amateur skill, or rather preference for functionality, is in the fenestration on the southern elevation of 185 Liberty. This is clearly done in the established building (contd.)

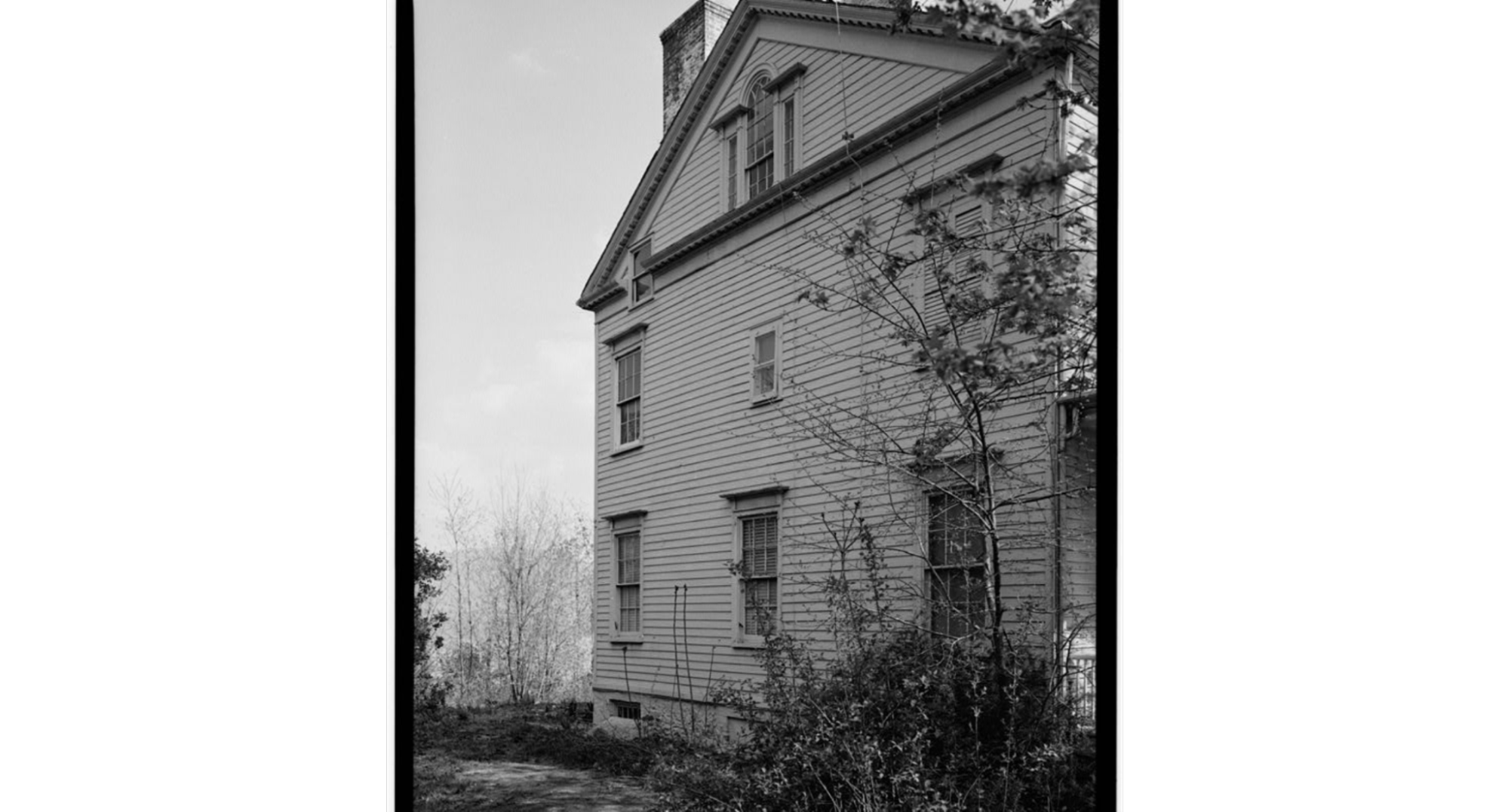

Figure 8 South elevation, Reeve house. (Tom Daley, Historical Society of Newburgh Bay and the Highlands)

Figure 9 Side elevation, William Roe House

(1826), 160 Grand Street, Newburgh, NY. (Library of Congress)

tradition, seen as recent as the Reeve house (Fig. 8) and earlier, in the Federal style William Roe House (1826) (Fig. 9). The windows are rectangular, spaced evenly, and two external chimneys flank the central bay of windows.

Vaux almost never treated an elevation this way, but one example McClung would have seen is in the Robert L. Case House (1853) at Grand and Broad Streets (Fig. 10). The northern elevation of this house resembles that known to the practical Newburgh carpenter contemporary with it, yet Vaux selects a window hood, circular opening, and peaked gable in the central bay to add variety. He also places the chimneys elsewhere and uses variations of wooden window casing. These remedy the monotony of this elevation, which faced a section of the neighborhood scarcely settled.

Besides this elevation, in the Case house is also seen Vaux’s method of window “stacking,” notably in the projection, which maintains a kinship with the McClung’s First Street house.

Figure 10 Calvert Vaux, Robert L. Case House (1853),

333 Grand Street, Newburgh, NY. (Villas and Cottages)

The Case and Moore houses were perceived as innovative to Newburgh builders for the diversity of their fenestration, though not always emulated correctly. Moore’s house, the earliest, altered the way architecture occurred in Newburgh, namely through Vaux’s decisions about windows. As Moore was a lumber dealer and hosted clients in his home office, it is highly probable McClung visited the house himself in 1853.8 There, he inspected the windows, and observed later the massing, or broader assemblage of architectural forms, further down the street at Case’s house.

Massing

Cross gable houses did not become a standard in Newburgh architecture until Downing’s publication of such plans in The Architecture of Country Houses (1850). Vernacular instances surely existed, but the formation of a projection in such an exercise as 185 Liberty was not considered as belonging to a style. Examples in English pattern books reached Newburgh via Downing in the very late 1830s and early 1840s, possibly explaining the Reeve house, but it is likely 185 Liberty has one of the first massings of its kind in Newburgh not designed by a professional architect.

In The Architecture of Country Houses, Downing produced two cross gabled farmhouse designs with the assistance of Alexander Jackson Davis. Both use jerkinhead roofs, which he believed were suitable for the countryside, and feature dormers in a similar position to those at 185 Liberty (Figs 11 and 12).9 In the “American style” farmhouse, interestingly differentiated from the English by use of wood, a prefiguration of Vaux’s window organization on the Moore house is seen on the projection and a side elevation, implying Vaux came to use the technique from Downing’s instruction.

The two plans seem to have merged in the years after their publication, and cemented themselves (contd)

Figure 11 Andrew Jackson Downing, Design XVI “A Farm-House in the English Rural style.” (Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses, 1850)

Figure 12 Andrew Jackson Downing, Design XVII “A bracketed Farm-house in the American Style.” (Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses, 1850)

Figure 13 Charles King House (ca. 1853), 232 Washington Street, Belmont, MA. (MACRIS)

Figure 14 Benjamin B. Odell, Sr. House (ca. 1853), 188 Grand Street, Newburgh, NY. (Urban Archive)

Figure 15 Views of house (ca. 1860) at 98 Lander Street, Newburgh, NY. (Tom Daley, Historical Society of Newburgh Bay and the Highlands)

as another highly-copied Downing plan, one example in practice being the Charles King House (ca. 1853) in Belmont, Massachusetts (Fig. 13). A smaller dormer has noticeably been added above the door to balance the weight of the projection and wall dormer at the opposite end, perhaps a variation from another pattern book mimicking Downing. 10

Two Newburgh houses near contemporary with 185 Liberty Street follow the same massing, containing elements possibly attributable to S. & J. McClung. The first is a demolished frame house built in the early 1850s and for much of the 19th century home to Benjamin B. Odell, Sr. (1825–1916). Odell was a businessman, later a city mayor, and father of future state governor Benjamin B. Odell, Jr. (1854–1926). A house on the Odell property first appears on the 1854 map, and it can be assumed the owner commissioned it recently, as it has similarities in massing to the Case house.11 The chimney construction, topped by brick dentils, is also copied from the Case house. A strong comparison may be made between the paneling of the bay window and that found in 185 Liberty’s bay window, suggesting the McClungs at work.12 Additionally, the south gable of the Odell house is identical to 185 Liberty, taking an outline similar to the jerkinhead gables in Downing’s plans (Figs. 11, 12, 14).

A final residence in this period worth noting is one currently (2022) being restored at the corner of Lander and Third Streets, built ca. 1859–1861. Often attributed to Downing & Vaux, or Withers, the house is unquestionably the work of a builder following the McClungs, if not the firm itself. A similar gutter system, slate patterns, and gable (seen on the rear wing) are present in 185 Liberty, but the house is more condensed in its massing than the attributable examples previously examined.

In closing this argument—which attributes 185 Liberty Street to builder James McClung—architect Calvert Vaux has been identified as a major source for Newburgh builders in the 1850s.

Calvert Vaux, Architect

A case that advocated for Calvert Vaux as architect of 185 Liberty Street could feasibly be made once the defender introduced “Ashcroft,” the Stephen H. Hammond House (1862) in Geneva, New York. The house still stands, and was apparently a larger remodeling project done to create a summer home. The front elevation of Ashcroft is almost identical to 185 Liberty Street, with the exception of the central dormer, bargeboards, and porch, as if Vaux was working to improve his hypothetically earlier plan. However, as pointed out, this massing and fenestration were not original, and had

Figure 16 Calvert Vaux, “Ashcroft,” the Stephen H. Hammond House (1862), Geneva, NY. (William Alex, Calvert Vaux: Architect and Planner, 1994)

become a solid design standard even by McClung’s time. It is unquestionable Vaux saw McClung’s house on Liberty Street, may have favored it, and replicated some of its features in a later work facing burnout. He has brought back the paired windows with mullions (at this commission in stone) and even installed turned spindles on the porch. In spite of these coincidences, Ashcroft is decidedly Vauxian in its bargeboards and roof construction, a hallmark of Downing & Vaux. In his bargeboard designs from the introduction to Villas and Cottages, comparisons may be found to Ashcroft, but not 185 Liberty Street, whose bargeboards are further dematerialized and airier. Vaux’s bargeboards tended to be composed of a single plank to which the carpenter applied shapes, carved outlines, or made piercings. Their ends often curved upwards, a trait considered “Rheinish” by Downing, who added them to the plan of a villa for The Architecture of Country Houses.13 To express the technical workings of the roof and its rafters, Downing & Vaux began adding brackets in their wall dormers where the roof and wall met (Fig. 17). Brackets of such function do not appear in 185 Liberty or

Figure 17 Vaux, Detail of wall dormer with bargeboard and brackets, Hammond house. (Hobart and William Smith Colleges Archives)

McClung’s First Street house, as he did not understand the firm’s theory behind their placement and considered them trivial.

Design No. 3 and the Cross Gable Floorplan

Though Ashcroft never appeared in Villas and Cottages or its subsequent revisions,14 one cross gable plan from Vaux’s period as a solo architect does. He calls the plan a “cottage,” that Newburgh mechanics estimated to cost $4,000 in 1852.15 The date and this design’s unexecuted status eliminate the possibility of its relation 185 Liberty Street, though the matter of its chimney placement could be cause for speculation.16 Vaux explains his unusual exterior placement of the chimneys as a matter of convenience, though as “a general rule,” he shares, “it is desirable in this climate [Newburgh] to build the chimneys in the body of the house, and not in the outside walls.” 17 Even with ample space to locate the chimneys interiorly, the designer of 185 Liberty out of impulse moved two stacks to the exterior walls.

Devising an estimate as to the purposes of each room on the first floor of the house is challenging with alterations. In its form, and perhaps most explicitly on the third floor, 185 Liberty Street is divided into four square rooms per story, another holdover from Georgian and Federal style plans. Newburgh cases including the David Crawford House typically saved one of the four squares for service purposes; in the Crawford house, the southwest square was a butlers’ pantry, nearest the kitchen steps.

Vaux maintained little care for these dated floor configurations he had known in English and American architecture. In his plan, the parlor and living room doors are made symmetrical and purposeful (Fig. 19). In 185 Liberty, the doors are subservient to the action of the staircase, which dominates the hall in its tight curvature. Vaux, after Downing’s preferences, placed staircases within their own spaces, separated from the living action of the domestic sphere. This gave practical room for the entrance hall to operate as an area of circulation or even celebration, denying the vanity Georgian

Figure 18 Vaux, Design No. 3, “A Suburban Cottage” (Villas and Cottages)

Figure 19 Vaux, Floorplans for Design No. 3 (Villas and Cottages)

builders induced by shoving staircases at the entry to boast prestige, as in the Crawford house’s curved and cantilevered staircase, an engineering feat in the village when constructed. Vaux & Withers’s Halsey Stevens House (1855) at 182 Grand Street presents one of these conspicuous types of staircases—unusual for Vaux in such a large house. Even the spindles and newel post of the Stevens house are sharper than those in 185 Liberty Street: the difference between a professional firm and self-appointed carpenter. 18

Footnotes

-

8’ is the distance traditionally recorded in the deeds, which stipulate that no structure can be built between its end point and the stone curb of Liberty Street. This effort guaranteed a uniform sidewalk width and set a precedent for new construction on the street. A precedent is Quality Row (1836), the five Greek Revival style townhouses on First Street’s north side, constructed with ample room for a stoop and sidewalk. ↩

-

John Little’s List of Works, compiled by himself in the 1880s, Newburgh Historical Society. ↩

-

Reeve later commissioned Vaux & Withers to design him a villa, but never built it. An issue with the date of the Reeve house is its appearance on Perris’ 1854 map; its outline is drawn as rectangular, without the side projection. This issue also occurs in the supposed outline of 185 Liberty, which shows the projection’s rear, but not its frontage at Liberty Street. It may be an error in recollection on the cartographer’s part, but some other houses, perhaps those more attractive, were given precise outlines. ↩

-

Calvert Vaux, Villas and Cottages (New York: Harper Bros, 1857), 213–18. The Moore house is Design No. 16. It is not likely Downing saw the house completed, but he probably planned the elaborate grounds before his death. ↩

-

The house does not appear on the 1854 or 1859 maps of Newburgh, but its land belonged to John Harris in the 1850s, adjoining the property and mansion of Benjamin Carpenter. According to Mary McTamaney, when the house was photographed in the 1950s for urban renewal documentation, it was owned by K & S Properties, Inc. On the 1870 city map it is marked as the property of a “Mrs. Ketley.” ↩

-

The tripartite window is also derived from the Palladian window, developed in the Italian Renaissance and later used in English classicism. Vaux would have known the Palladian window as a standard design element in his training, but the window was instated prominently in such Newburgh buildings as the David Crawford House (1830) at Clinton and Montgomery Street. ↩

-

Vaux would use a paired window with wooden mullion again on the second floor of his Halsey Stevens House (1855), 182 Grand Street, Vaux & Withers. Though the Stevens house omits window hoods or bays on the street-facing elevation, the rising, or pyramidal outline, is enforced by tripartite windows at the ground floor divided by brick mullions. The brick is captivating and spreads each window apart further. ↩

-

The home office was on the ground floor; its hooded entrance is visible to the side in Fig. 4, perhaps the destination of the human figures. ↩

-

One cottage of this nature appeared in a later edition of Downing’s Cottage Residences published while the author was still alive: Design XI in the 1873 edition, “A Cottage for a Country Clergyman.” ↩

-

This choice, repeated in 185 Liberty, may also be an independent realization by the builders, who saw this large unfilled space and felt it needed interest. These small dormers are not truly functional. ↩

-

Compare the illustration of the Case house from Villas and Cottages, 159 (perspective view, the elevation seen traveling north on Grand Street), with the photograph of the Odell house in John J. Nutt, Newburgh: Her institutions, Industries and Leading Citizens (Newburgh: Ritchie & Hull, 1891), 280. ↩

-

In the house owned by Odell and the First Street house, the bay windows are rectangular, making 185 Liberty’s bay window all the more unique. ↩

-

See Design XXXII “A Lake or River Villa for a Picturesque Site” in The Architecture of Country Houses. ↩

-

Editions of 1864 and 1874. ↩

-

$134,839.98 in 2021. ↩

-

Vaux, Villas and Cottages, 123–125. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

It is worth noting the door casing in both the Stevens house and 185 Liberty are the same; Newburgh door casings and moldings began to become extremely elaborate with the arrival of mason Franklin Gerard in the late 1850s. Gerard was the mason and plasterer for the William Fullerton House (1859–60) at 297 Grand Street. ↩